Welcome to the Mathematical World!

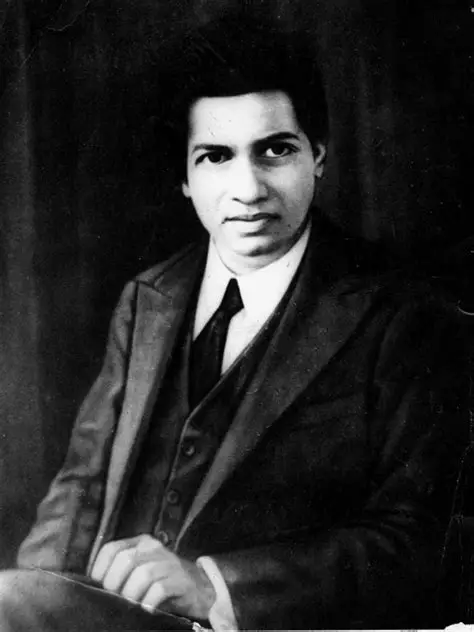

Srinivasa Ramanujan

Indian Mathematical Prodigy and Pioneer of Number Theory

Srinivasa Ramanujan (1887 – 1920) was born on December 22, 1887, in Erode, a small town in Tamil Nadu, India. His father worked as a clerk in a cloth shop, while his mother was a homemaker deeply involved in religious traditions. Growing up in poverty, Ramanujan had little access to books or formal education, but he displayed an astonishing talent for numbers at a very young age. By the age of 12, he had mastered advanced trigonometry, and by 15, he had independently developed results from G. S. Carr’s A Synopsis of Elementary Results in Pure and Applied Mathematics, a book containing thousands of theorems without proofs. With little formal training, he spent his teenage years filling notebooks with formulas, identities, and infinite series that he derived through intuition and deep insight. According to Hans Eysenck, "he tried to interest the leading professional mathematicians in his work, but failed for the most part. What he had to show them was too novel, too unfamiliar, and additionally presented in unusual ways; they could not be bothered."

Ramanujan’s genius covered a wide range of fields in pure mathematics: number theory, infinite series, partitions, and modular forms. He developed highly original results in the theory of prime numbers and devised remarkable formulas for approximating \(\pi\). For example, one of his most famous series, which was later used in computer algorithms to calculate billions of digits of \(\pi\), is:

\[ \frac{1}{\pi} = \frac{2\sqrt{2}}{9801} \sum_{k=0}^{\infty} \frac{(4k)!(1103+26390k)}{(k!)^4 396^{4k}} \]

He also made pioneering discoveries in partition functions. Ramanujan, along with G. H. Hardy, developed the celebrated Hardy–Ramanujan asymptotic formula for the partition function \(p(n)\):

\[ p(n) \sim \frac{1}{4n\sqrt{3}} \exp\!\left( \pi \sqrt{\frac{2n}{3}} \right) \]

This work laid the foundation for modern combinatorics. In his later years, Ramanujan introduced “mock theta functions,” which baffled mathematicians for decades until they were connected with modern string theory and modular forms in the late 20th century. His notebooks, filled with thousands of identities and results, continue to be studied even today.

In 1913, Ramanujan wrote to the British mathematician G. H. Hardy, enclosing samples of his work. Though many results seemed incredible at first glance, Hardy recognized Ramanujan’s brilliance and invited him to Cambridge University. There, Ramanujan flourished, publishing groundbreaking papers between 1914 and 1919. Despite cultural differences and health struggles, the collaboration produced famous results such as the Hardy–Ramanujan theorem, research on highly composite numbers, and work on divergent series. In his notes, Hardy commented that Ramanujan had produced groundbreaking new theorems, including some that "defeated me completely; I had never seen anything in the least like them before", and some recently proven but highly advanced results.

Ramanujan’s life was tragically short; he died on April 26, 1920, at the age of only 32, likely due to tuberculosis and malnutrition. Yet his influence has been monumental. During his short life, Ramanujan independently compiled nearly 3,900 results (mostly identities and equations). His discoveries continue to inspire new research, and many of his formulas have found surprising applications in physics, computer science, and even black hole theory. His “Ramanujan primes” and “Ramanujan numbers” (such as the famous taxicab number 1729, the smallest number expressible as the sum of two cubes in two distinct ways) remain part of mathematical folklore.

Ramanujan is celebrated as one of the greatest minds in mathematics. In 2011, the Government of India declared December 22 as National Mathematics Day. His story of raw genius, nurtured against all odds, continues to inspire generations of mathematicians worldwide. The Ramanujan Journal, established in 1997, is dedicated to areas influenced by his work, and his legacy lives on as a symbol of the power of human intuition in mathematics.